Regardless of whether you’re a first or a fourth-year optometry student, glaucoma is something we all must become familiar with for our profession. Though most optometry students spend a significant amount of time learning about the glaucoma, it’s a topic worth revisiting regularly, which is why we’ve got a quick guide that you can easily reference to help make your diagnosis.

It is important to remember that glaucoma is a disease of asymmetry! One of the biggest misconceptions is that having glaucoma means the pressure in the eye is really high. It is important to distinguish high intraocular pressure (IOP) versus pressure that is too high for the patient.

The Basics: Glaucoma vs. Ocular Hypertension

A Sick Optic Nerve: Glaucoma is a group of neuropathies. In other words, glaucoma is a group of disorders whose common denominator is having a sick optic nerve. But you probably already know this. Just like you know that having glaucoma leads to a loss of ganglion cells, changes in the anatomy of the optic nerve and, ultimately, vision loss.

Ocular Hypertension: This condition refers to the trend of having intraocular pressure that is consistently higher than 21 mmHg without any accompanying signs of glaucoma on OCT testing or visual fields. At this point, the optic nerve will appear normal and without cupping. However, there is such a strong correlation between increased pressure and optic nerve damage that many doctors will monitor these patients for glaucoma or even start treatment with eye drops to reduce the chance of the patient developing glaucoma.

Open Angles

With Open Angle Glaucoma, the patient has developed damage to the optic nerve, but the iridocorneal angle isn’t found to be clogged, closed or damaged.

Open and Clear

Primary Open Angle Glaucoma (POAG): When people think of glaucoma, they often default to thinking of an open angle with increased intraocular pressure. POAG is characterized by pressure above the cutoff of 21 mmHg and signs of optic nerve damage.

Normal Tension Glaucoma (NTG): In this condition, IOP is within the accepted normal range of 10-21 mmHg, but there is still damage to the optic nerve that is consistent with the pathophysiology of glaucoma. Research is ongoing as to exactly why this happens, but it is important to recognize that the pressure in NTG, while within normal range, is still considered too high for that particular patient. In the meantime, lowering the IOP further has been the preferred treatment.

Inflamed, Clogged or Damaged

In these subtypes of glaucoma, a clogged or damaged angle leads to poor drainage of aqueous humor, which then leads to increased IOP.

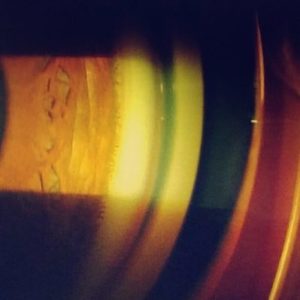

Pseudoexfoliation (PXF) Syndrome: Increased pressure caused by white, flaky deposits that clog the angle. You can also see these deposits on the pupillary margin and around the lens capsule. Patients with PXF can have pressures that rise dramatically in a short period of time. This is one of the most common causes of secondary glaucoma worldwide, so patients with uncharacteristically high pressures should be checked for these fibrillar deposits and brought back for follow-up sooner than once a year to be closely monitored for glaucomatous changes. (Note: you may also observe poor pupillary dilation due to the structural damage to the iris from the debris.)

Pigment Dispersion: True to the name, the problem in pigmentary dispersion syndrome is, well, pigment. In pigmentary dispersion syndrome, pigment from the iris is being disturbed by the lens zonules and may end up clogging the trabecular meshwork. Unlike with pseudoexfoliation syndrome, you’ll see transillumination defects in the iris with this type of glaucoma.

Angle Recession: This is an angle that has experienced trauma in the past. The observed angle will appear wider than normal on Van Henrick and gonioscopy. If the trauma has damaged the trabecular meshwork, glaucoma may develop several years after the incident.

Posner Schlossman: This is mild or minimal inflammation with a big spike in IOP. While we’re still learning about the etiology and causes of the disease, we do know that the inflammation effects the trabecular meshwork, causing trabeculitis. Multiple instances of inflammation and subsequent IOP spikes will damage the optic nerve causing glaucoma.

Fuch’s Heterochromic Iridocyclitis: This is actually a unilateral and chronic inflammation of the iris and ciliary body. Over time, the bouts of inflammation can damage the trabecular meshwork leading to glaucoma.

Phacolytic Glaucoma: In this variation, lens particles from a hypermature cataract are clogging the angle. Surgery to remove the cataract should improve both the vision and the IOP.

Iridocorneal Endothelium (ICE) Syndromes: These include essential iris atrophy, Chandler’s Syndrome, and Cogan- Reese. While each of these diseases varies slightly, they all may cause glaucoma because the corneal endothelium begins to proliferate causing a blockage in the trabecular meshwork.

Closed Angles

Glaucoma caused by angles that are not considered to be open 360 degrees.

Anatomically Closed Angle or Primary Angle Closure Glaucoma

Physiologically Narrow Angle: This is an angle that is anatomically narrow and are therefore prone to closure when the pupil is dilated. In clinic, you’ll see that the Van Henrick angle is a 1 or 0 in these patients and should do gonioscopy to confirm. These patients are also more likely to complain of headaches or, in rare cases, even stomach discomfort after being in a dim room. These are also patients to be very careful with when you want to dilate the eye. A physiologically narrow angle may be due to a pupillary block or a plateau iris. Know the difference between these two causes because only one of them can be fixed with a Laser Peripheral Iridotomy (LPI).

Closed Angle Due to Other Causes

Neovascular Glaucoma (NVG): Blood vessel growth on the iris and trabecular meshwork pulls the angle shut. This is often due to an ischemic event in the back of the eye but can also be due to proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Gonioscopy will reveal the extent of neovascularization and is especially worrisome if the vessels migrate anteriorly beyond the scleral spur.

Uveitic Glaucoma: A sticky, swollen iris may attach itself to the endothelium of the cornea (forming an anterior synechia) or the anterior portion of the crystalline lens (forming a posterior synechia). Either development can lead to an occlusion in aqueous outflow.

While glaucoma is complex, there are several ways to break this disease down in your mind in order to make it easier to remember. However you choose to organize glaucoma in your mind, it is definitely something that you’ll be seeing throughout your career as an optometrist, so make sure you have the resources to easily rule out the type of glaucoma based on clinical signs and symptoms.