By Faba Varghese, University of the Incarnate Word, Rosenberg School of Optometry

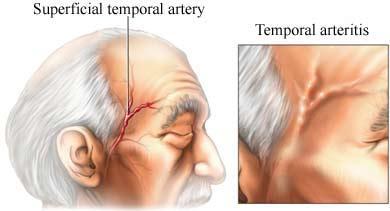

Giant cell arteritis (GCA) is an ocular emergency due to the increased risk of severe vision loss if left untreated.1 It is a granulomatous inflammation of various arteries, most commonly the superficial temporal artery, the ophthalmic artery, the posterior ciliary arteries, and the vertebral arteries. This condition is most frequently seen in elderly, white women (70 years and older).1

Signs & symptoms

Most common systemic signs/symptoms include scalp tenderness, headache, and jaw claudication. Less common signs/symptoms include weight loss and fever.1

A common ocular symptom is vision loss (or amaurosis fugax), which is usually caused by either Arteritic Anterior Ischemic Optic Neuropathy (AAION) or CRAO. Other symptoms may include diplopia and ophthalmoplegia. Ocular signs include: disc pallor, disc edema, disc hemorrhages and/or cotton wool spots.1

Diagnosis criteria

In 2022, the American College of Rheumatology made a classification criteria for GCA. That being said, there’s no one diagnostic criteria nor sign/symptom that is pathognomonic for GCA.1

The classification criteria is as follows1:

- Age ≥50 years at diagnosis (absolute requirement)

- Score of ≥6 points, considering:

- Positive temporal artery biopsy or temporal artery halo sign on ultrasound (+5)

- Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate (ESR) ≥50 mm/hour or C reactive protein ≥10 mg/L (+3)

- Sudden visual loss (+3)

- Morning stiffness in shoulders or neck, jaw or tongue claudication, new temporal headache, scalp tenderness, temporal artery abnormality on vascular examination, bilateral axillary involvement on imaging and fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography activity throughout the aorta (+2 each).

Testing

Although a definitive diagnosis is not needed before initiating treatment, testing must be performed soon after to solidify the diagnosis.

Testing includes1:

- Temporal artery biopsy (gold standard)

- A positive result can be seen a week to a month after starting steroids.

- Bloodwork: Immediate ESR, CRP, Platelet count

- Pupillary testing, color plates, and a DFE for nerve assessment are all additional testing (not diagnostic) but are performed to rule out any other possible causes of visual loss.

Treatment

Steroid treatment should be started immediately if GCA is suspected, even if diagnostic testing has yet to be performed. As recommended in Wills Eye Manual, Intravenous Methylprednisolone 250 mg should be administered q6h for 12 doses, followed by oral prednisone 80-100 mg oral daily for at least 6 to 12 months.3 While there is currently no standardized corticosteroid treatment, patients at a higher risk for severe vision loss or with cerebrovascular disease should be given a higher dose. Furthermore, an antiulcer medication such as proton pump inhibitors or histamine type 2 receptor blockers as well as an osteoporosis prevention medication should be considered in these patients. Some other treatments that are currently being investigated include anti-interleukin-6, TNF-a blockers,

IL-12/IL-23 blockers, IL-1b blockers, and T-cell mediated CD 28 blockers.1

It is also recommended to collaborate with the patient’s PCP and/or rheumatologist for management of steroid side effects.2

Takeaway

GCA is an inflammatory condition that needs immediate assessment and treatment, which can be started before a true diagnosis is made. Recognizing and following the appropriate steps in an emergent condition can prevent further vision loss and help to maintain a patient’s quality of life.

References

- Barmettler, Anne. “Giant Cell Arteritis.” Eyewiki, 3 Apr . 2024, https://eyewiki.aao.org/Giant_Cell_Arteritis

- Lee, Andrew G. “Giant Cell Arteritis.” YouTube, YouTube, 1 Apr. 2019, www.youtube.com/watch?v=McbiRK_0KGE.

- Bagheri N, Wajda BN, Calvo CM, et al. The Wills Eye Manual: Office and Emergency Room Diagnosis and Treatment of Eye Disease. 7th edition. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Wolters Kluwer; 2017. Pg 397. Accessed April 28, 2024.

- Special thanks to Dr. Ribisi for her review and feedback when writing this article.